Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) exhibit a critical tendency to produce hallucinations, resulting in content that is inconsistent with real-world facts or user inputs. This phenomenon poses substantial challenges to their practical deployment and raises concerns over the reliability of LLMs in real-world scenarios, which attracts increasing attention to detect and mitigate these hallucinations. Recent work successfully proved that hallucinations can be detected in the internal states of a large language model, by training a lightweight classifier to that matter. To take this work one step further, we designed a classifier-guided beam search algorithm at a statement level that intends to use their knowledge at inference time to reduce the probability of generating text containing a hallucination. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach by comparing LLama2-7B performance with and without it. Classifier-Guided Beam search can hold an improvement of around 3% on StrategyQA and CommonsenseQA and 1% on TruthfulQA compared to a baseline generation method.

Fundamentals and Related Work

1. Open-ended Text Generation

When given an input sequence of tokens \(x\), language models perform open-ended completion by generating the next tokens that are the most likely to follow \(x\) until reaching the EOS token (End of Sentence). Formally, it involves generating the next \(n\) tokens to obtain the completed sequence \(x, y_1, \ldots, y_n\). Modern Large Language Models do it in an autoregressive way, assuming that the language model computes \(P(y_{1:t}, x)\) using the left-to-right decomposition of next token probability. Based on the chain rule of probability and the Markov assumption, the decoding objective maximized while generating the completion at time step \(T\) becomes:

$$P(y_{1:T}) = \prod_{t=1}^{T}p(y_t \mid y_{1:t-1}, x)$$

One of the most commonly used sampling algorithms to generate a text that would maximize this objective function is the beam search algorithm. Instead of employing a greedy approach that simply picks candidates with the highest probability at each step, Beam search proceeds stochastically, selecting from the top-k tokens based on their normalized probabilities. This method efficiently navigates through the search space, allowing for the simultaneous consideration of multiple potential continuations of the input sequence.

At each decoding step, beam search maintains a set of searching paths, or beams, of size K, where K is the beam width, and selects one candidate sequence from N ones for each beam.

2. Constraining the Objective Function

Guiding the decoding process to make the model generate specific types of answers can be done simply by adding a numeric constraint to the objective function. For instance, Xie et al. introduced a stepwise self-evaluation mechanism to guide and calibrate the reasoning process of LLMs. They defined a constraint function \(C(s_t, s_{1:t-1}) \in [0, 1]\) within each step, which consisted of a confidence score in the correctness of the reasoning sequence \(s_t\) based on the previous context \(s_{1:t-1}\). The constrained decoding objective function \(E(s_{1:T})\) that combines the language model probability and the correctness confidence score is given by:

$$E(s_{1:T}) = \prod_{t=1}^{T} P_{\lambda}^{LM}(s_t \mid s_{1:t-1}, x)C^{1-\lambda}(s_t)$$

Here, \(P_{\lambda}^{LM}\) is the language model's probability distribution. \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\) is a weight hyperparameter to balance the LM score and the confidence score, which makes the log-transformed objective a weighted average of multiplied probabilities and confidence scores.

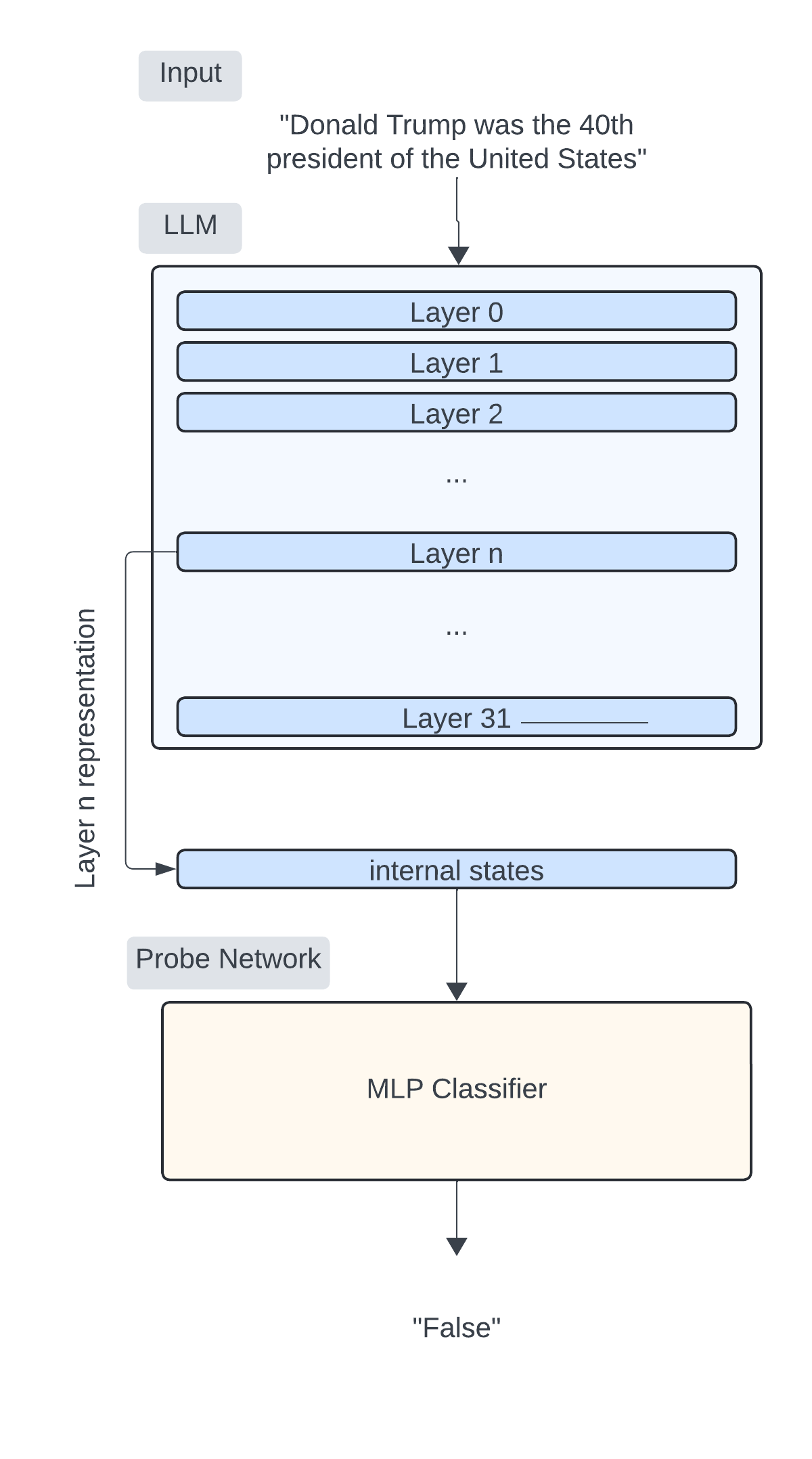

3. Hidden Layers Probing

In their work, Chwang et al. demonstrated that it is possible to predict the hallucinative behavior of a language model by probing its internal states with linear classifiers. Assuming that a language model generated the sequence \(y_1, \ldots, y_n\) in response to a context \(x\), probing the first layer would involve extracting the first hidden layer logits \(z_1^1, \ldots, z_n^1\) (all of dimension \(d\)) activated when generating the token \(y_n\). A linear classifier can then be trained to label the truthfulness of the sequence \(y_1, \ldots, y_n\) by taking \(z_1^1, \ldots, z_n^1\) as input and outputting True or False.

This follows an autoregressive factorization form, and thus traditional token-level decoding methods such as beam search can be applied here at the chain (sentence) level. While Xie et al. (2023)’s work successfully uses LLM’s self-evaluation to guide the generation, it is extremely computionally exhaustive doing inference when generating \(K\) beams and \(K × N\)candidates.

Three probe architectures are proposed and tested across tasks using both organic and synthetic hallucinations for annotation. The contributions include a dataset of 15k+ annotated utterances to train linear probes on, improved detection meth- ods, and an analysis of factors affecting accuracy. (Azaria and Mitchell, 2023) take the same approach and conclude with similar findings, nevertheless they trained their probes on more generalistic facts and conducted an insightful ablation study show- ing which layers get the best results when probing Llama2 (Touvron et al., 2023).

4. True/False Statements

Previous work has narrowed the scope of LLM probing to specific tasks, such as abstractive summarization, knowledge-grounded generation, and data-to-text generation. However, the focus on factual statement verification is relatively new. The FEVER dataset is a publicly available resource for fact extraction and verification against textual sources, consisting of 185,445 claims manually verified against Wikipedia pages.

Eliciting Hallucination via Chain of Thoughts and Step-wise Probing

Assuming access to a white-box language model \(LM\) and a probe classifier \(C\) capable of giving reliable predictions on the truthfulness of a sequence of activation logits, we propose a method to reduce hallucinative generation by guiding the decoding process. Given the strong results showcased by chain of thought reasoning, we hypothesize that the truthfulness of answers generated by the model can be improved by forcing the generation of intermediarily true statements before the final answer.

In a QA format, our generation method involves forcing the model to generate \(T\) statements before giving a final answer. At each timestep, \(K\) candidate statements are generated following standard methods, and the model's internal activations are retained. The truthfulness of each candidate statement is then assessed by the probe \(C\). To construct the final answer, we apply a classifier-guided beam-search on a statement level. The objective function that is maximized makes parallel use of both the generation probability computed by the language model and the probe prediction to guide the generation process toward a truthful answer.

At time-step \(t\), the score of the k-th statement given context \(x\) is computed as follows:

$$S(s^t_k, x) = P_{LM}^{\lambda}(s^t_k, x) \cdot C^{1-\lambda}(s^t_k)$$

With \(C(s^t_k)\) being the probability that stk contains no hallucination,\(P_{LM}^{\lambda}(s^t_k , x)\) the likelihood of statement \(s\) (computed by the Language Model), and \(λ\) a hyperparameter, the composed score is then transformed into probabilities via softmax and guides the random selection among all candidates of a single beam. For instance, here is a detailed walk through of the method given the context: Donald Trump was elected in 2017.

Methodology

1. Dataset

To achieve our goals, the first step was to gather a sufficiently large and robust dataset comprising both factual and hallucinative statements. In line with previous work, we extended the True-False dataset with the FEVER dataset to ensure a more comprehensive data coverage. Additionally, we extracted approximately 6,000 verified facts from the StrategyQA corpus and prompted GPT-3.5 to generate false statements from each fact. To facilitate a more nuanced analysis of our find- ings, we categorized our dataset and evaluation datasets into five distinct application subcategories: Health and Medicine (1961 datapoints), Humani- ties (4932 datapoints), Natural Sciences (4258 dat- apoints), Social Sciences (4957 datapoints), and Technology and Engineering (4300 datapoints). The assignment of each utterance to its respective category was achieved through zero-shot classifica- tion facilitated by GPT-3.5 (Appendix A.1). A representative excerpt from our dataset is pre- sented in Tables 1 and 2, illustrating examples of True and False Statements.

Examples of True Statements

| Category | Example of True Statement |

|---|---|

| Health and Medicine | Lyme disease infects those affected by it. |

| Humanities | Specific art forms were banned in Nazi Germany. |

| Natural Sciences | The Greenland shark is also known as the grey shark. |

| Social Sciences | Quentin Tarantino works in the movie industry. |

| Technology and Engineering | Monkeys can be trained to push buttons. |

Examples of False Statements

| Category | Example of False Statement |

|---|---|

| Health and Medicine | A doctorate takes an average of 3.5 years. |

| Humanities | Everton F.C. is not a football club. |

| Natural Sciences | Iceland is not volcanically active. |

| Social Sciences | Seppuku is a Korean ritual. |

| Technology and Engineering | Apple was founded in 1979. |

2. Probing LLMs

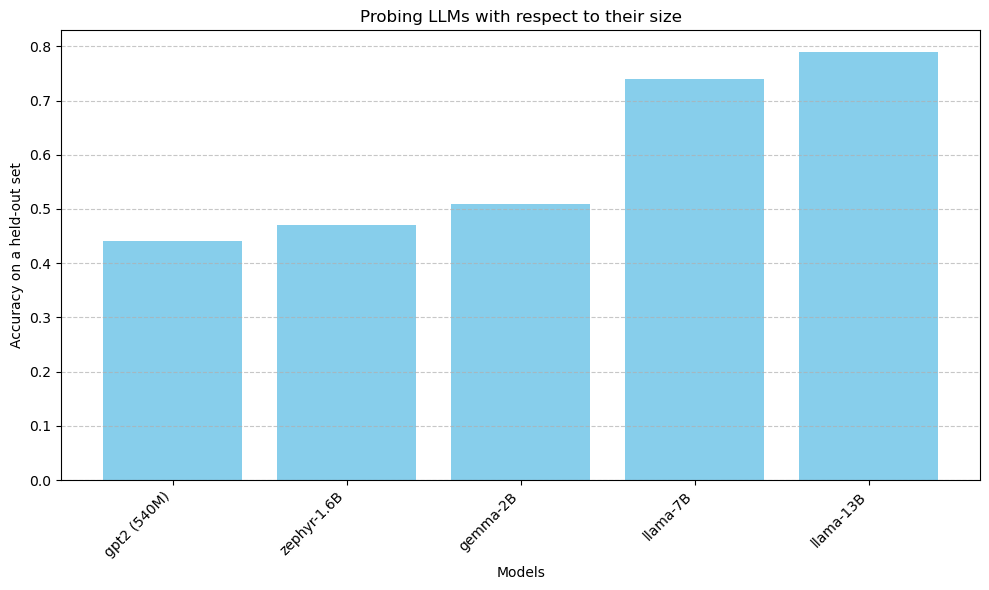

Following dataset mapping, we conducted a series of experiments involving the GPT-2, Zephyr1.6B, Llama2-7B, and Llama2-13B models. Probes were trained on all layers for each model, and the results were meticulously compared to select the best one for our experiments. Our attention ultimately gravitated towards the LLama2-7B model due to its provision of the most accurate and generalizable results across our validation dataset and also for the sake of computational resources saving. Unsurprisely, bigger models tend to be easier to probe. A fact that can be explained by the bigger dimensions in their internal states, providing the probes with more information encoded in the embeddings.

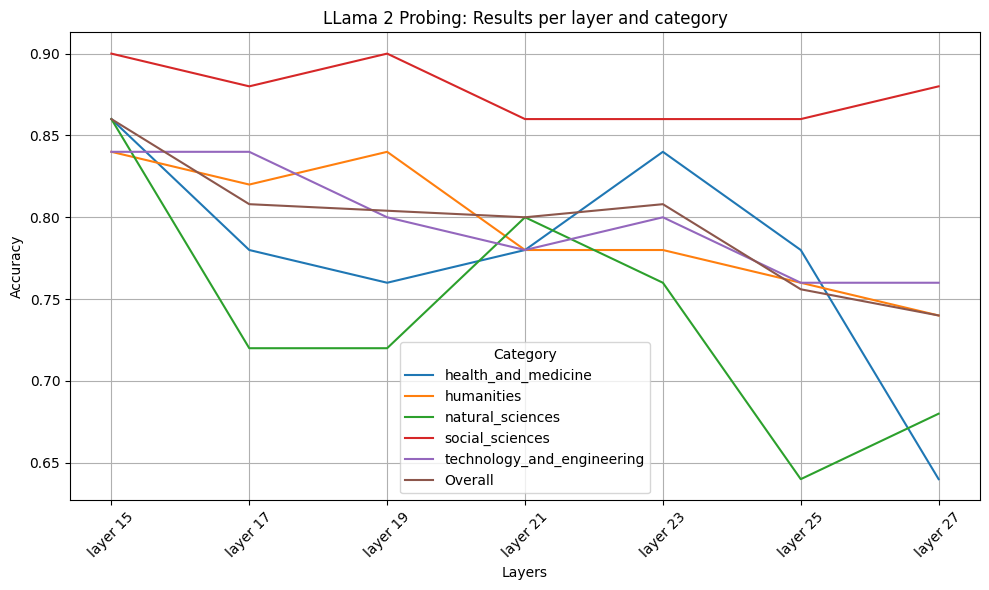

When probing, we aim to address the question: "Which layer's internal states contains the best information to detect hallucinations?". Quite similar to \citep{azaria2023internal} findings, in our experiments, we noticed that the deeper layers of Llama2 yielded better results on our custom dataset. In consideration of computational constraints, our final probe evaluation prioritized assessing layers within the latter portion of the LLama2 model. The 3 layers with the best overall accuracies were selected for the following inference process.

3. Guided Inference

To verify the effectiveness of the probes' guidance, we evaluate our method on three benchmarks: TruthfulQA, StrategyQA, and CommonSenseQA. During inference, we follow a benchmark-specific few-shot Chain-of-Thought prompt to make the model generate reasoning steps before final answers, where an expected step is a factual statement. At each timestamp, we perform real-time hallucination detection on the candidates with our pre-trained classifier, and the confidence score is adopted to guide the candidate selection.

With LLama2-7b as our language model, we use the original stochastic beam search as our baseline, where we set \(K =4\) and \(N =3 \) for beam search settings. For our guided beam search, the aggregation weight of model’s probabilities and confidence scores is set as \(λ = 0.5\) following Xie et al. (2023). As there exists potential gaps between the train- ing data used for probes and the real open-ended texts generated by LLMs, we also perform ablation study on the impact of various training data split to generation performance. As shown in the next table, S (Small) and L (Large) splits refer to the cases that we train the probe with and without FEVER partition, which is the most comprehensive part of our dataset. Since several studies also showed that different information was encoded in different layers of an LLM, we also explore the feasibility to ensemble

Results

1. Guided Beam-Search Performance

We show in this section thqt we get consistent improvement on all the benchmarks, and our method yields most significant enhancement on StrategyQA. It is reasonable considering the reasoning paths of StrategyQA consist more statements than others. The consistent improvement also indicates the transferability of the pretrained classifier trained with limited data, given the benchmarks are more sophisticated. Compared with single layer probes, the ensemble probes do not show obvious enhancement while they can alleviate the over-confidence discussed in the next section. Assuming a high quality classifier, guiding the generation with higher confidence should guide the search to more truthful candidates, and should not worsen the performance. This is corresponding to our observation. It is surprising that larger and more complex training data brings reduction to the generation performance. An explanation is the capacity of MLP as probes. The larger training data introduces more noise and induces the model to be over-fitting. Future work may explore larger models as more generalizable probes.

| Model & Benchmark | TruthfulQA | StrategyQA | CommonSenseQA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 33.58% | 65.13% | 19.40% |

| Guided-single-S | 34.06% | 68.94% | 20.11% |

| Guided-ensemble-S | 34.48% | 68.43% | 22.85% |

| Guided-single-L | 30.79% | 64.27% | 21.04% |

| Guided-ensemble-L | 31.66% | 65.75% | 19.51% |

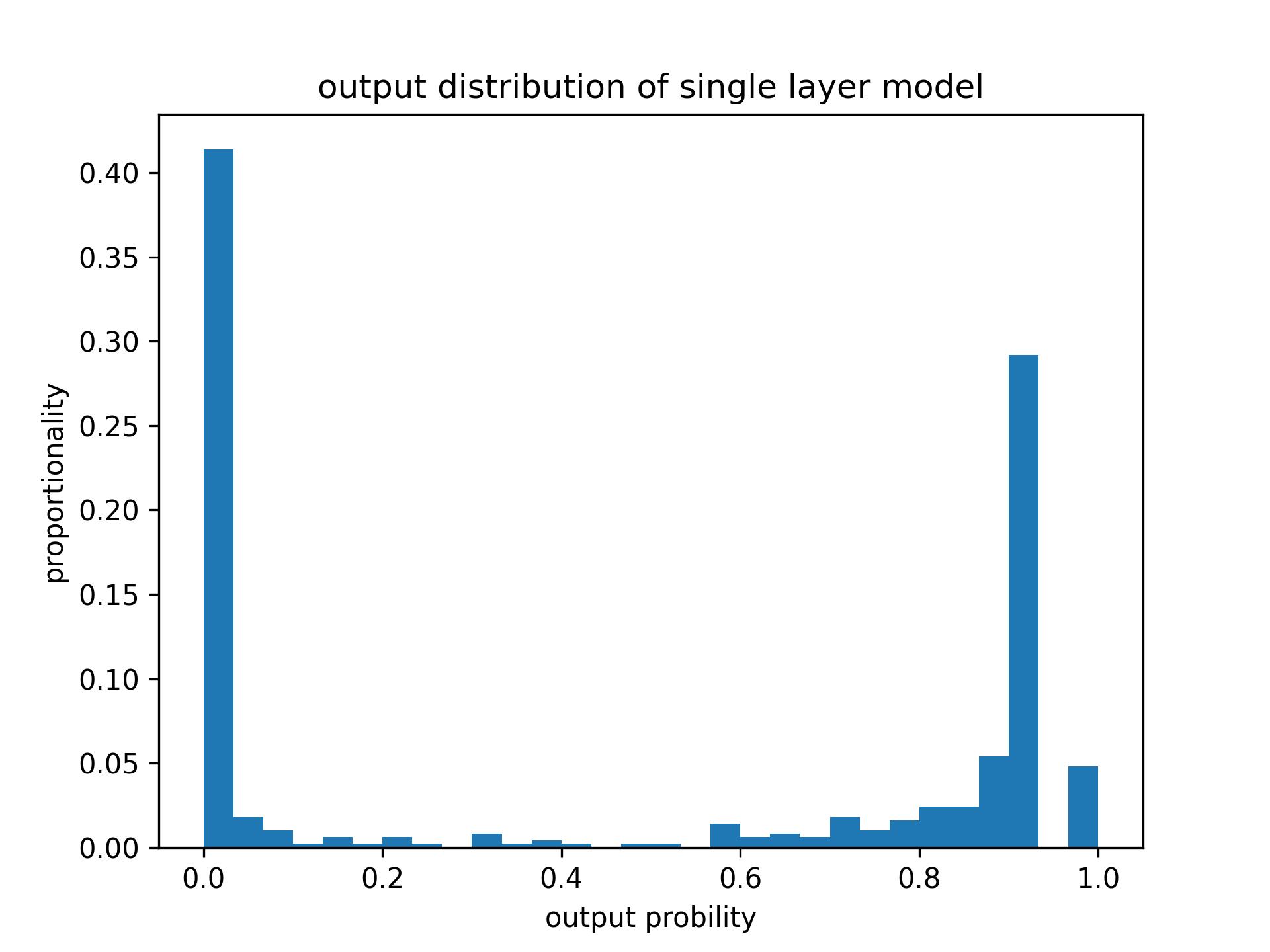

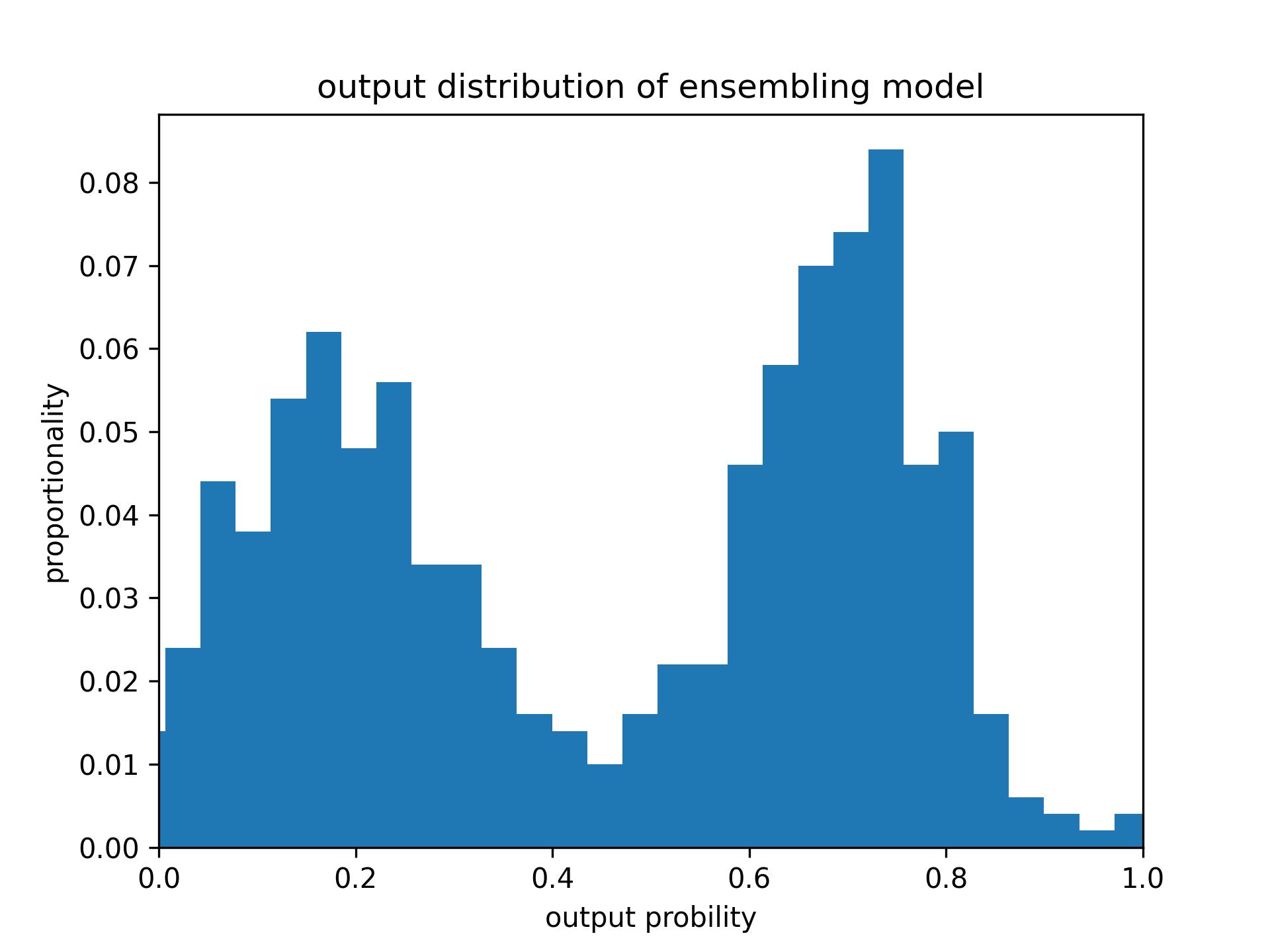

2. Over-Confidence in Hallucination Classification

We have ve observed a tendency towards over- confidence in the implementation of hallucination classifiers, where the probability distribution of classifiers tends to resemble a binomial distribution. To address this, we suggest two straightforward so- lutions to provide softer guidance. Our first approach involves ensembling the out- puts of multiple probes to mitigate over-confidence. Below, you’ll find the probability distributions of the outputs based on 500 samples: By ensembling multiple probes, the over-confidence is mitigated while maintaining the discriminality ability.

Another approach is introducing a temperature parameter T in the softmax layer to adjust the centrality of the output distribution. Larger temperature lower the gap of binary probabilities. We conducted an ablation study of the impact of this temperature parameter and showcased the results on StrategyQA, the results are shown in Table 5, where T = 2 yields best result.

| Temperature | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| T=1 | 68.13% |

| T=2 | 68.94% |

| T=5 | 67.39% |

| T=10 | 68.46% |

Conclusion and Discussion

In this work, we explore the feasiblity to reduce hallucinative statements generation by probing the hidden states of a model. We build a True/False statements dataset with categories and trained clas- sifiers with the extracted hidden states of differ- ent models. We find that bigger models tend to be easier to probe as the classification accuracies are higher. Then, we found that, for Llama2-7B, the middle layers are more suitable to detect hal- lucination on various topics. We then used the trained classifier to guide the generation of new text by tweaking the decoding objective function in the beam search. We tested our method on three benchmarks and got consistent improvement, while exploring alternative designs and parameters.

However, several critical questions remain for future exploration:

- The detection of hallucinations using hidden states is limited by the dataset used to train and validate our classifier. It's unclear which types of hallucinations cannot be detected across various models and why.

- The generalizability of classifiers is a significant challenge. Our classifiers exhibit unstable performance when trained with different data corpora. It's unclear whether increasing the model size of the classifier or modifying the training data could lead to more robust classifiers.

- There may be superior methods for integrating classifiers in generation or other applications that offer enhanced performance and robustness while imposing minimal computational overhead.